Henan University of Technology researchers report on the development of a lightweight lattice-based limb design for a bionic robot. Lightweight structures that can withstand high loads and torsion are in demand in a range of industries such as aerospace, shipbuilding, and robotics. Experimental thin-walled structures, honeycomb cores and lattice frameworks are being tested in search of a new generation of material forms.

In the study, “Research on lower limb lightweight of bionic robot based on lattice structure unit,” published in Scientific Reports, researchers claim to have created an innovative structural configuration library using topology optimization and applied it to the design of a bionic quadruped robot.

Unfortunately, the paper is unreliable. It is unclear if the paper has been poorly translated, unskillfully formatted, AI-manufactured, or simply contains errors that were missed by the authors, the peer-review process and the publisher’s editorial staff.

In the plausible error category, Evans et al. 2001 is incorrectly cited as being from 2000 and attributed to “Evana.” A minor error perhaps, but it appears in the introduction and is a basis for the study design, so we are not off to a good start.

Deeper into the study, things begin to get explicitly more problematic.

Twenty lattice structural units were established and Table 4 of the paper illustrates the relative density of all 20 lattice structures. This is a helpful reference as the paper will later misassign these relative densities across some units, conflating densities between key structures, and making contradictory claims about them.

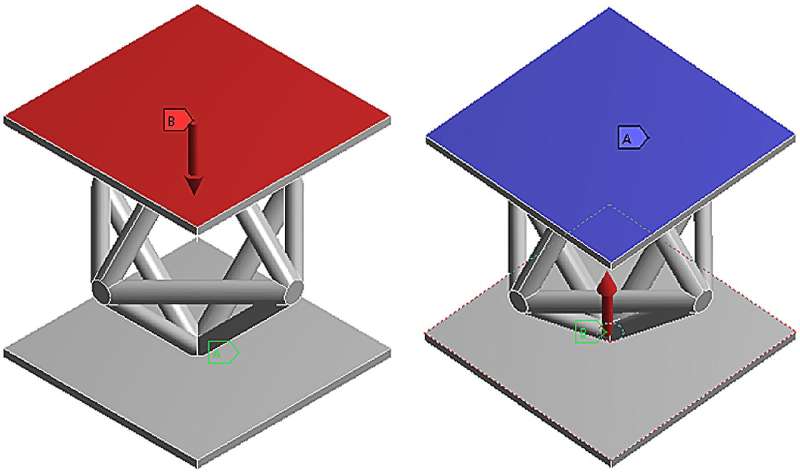

For example, the paper states that Figure 8 illustrates the bending response characteristics derived under bending conditions: “Among the lattice structures tested, unit No. 14 demonstrates the highest stiffness at 32.38. In contrast, unit No. 1 exhibits the poorest bending performance, with a maximum displacement of 3.65 mm, a relative density of 0.0942, and the lowest specific stiffness at 6.48.”

Based on the data tables included in the paper, No. 1 shows the third highest displacement (behind units 3 and 7), and the relative density of 0.0942 is previously attributed to No. 14 in Table 4, not to No. 1.

Elsewhere, the paper states that, “When subjected to torsion, the No. 14 lattice structure No. experiences a maximum displacement and deformation of 0.12 mm. With a relative density of 0.0842, it also exhibits the highest specific stiffness, at 97.44.” In this case, No. structure 14 is mistakenly given the relative density of No. 13, at 0.0842, not the listed 0.0942 for No. 14, as well as the data results of No. 13 for specific stiffness per Figure 9.

Other issues include either overstatements or lack of reporting, for example, the study states, “As detailed in Table 8, following optimization, the leg structure’s volume has been reduced by 23.03%, and its stiffness has increased by a factor of 1.97. Correspondingly, the overall weight decreased by over 23%.”

Based solely on the paper’s own supplied data of an initial structure weight of 0.36 kg and an optimized version of 0.29 kg, the weight decrease should be ~19.44%, not more than 23%. A stiffness increase by a factor of 1.97 seems unrelated to any of the supplied data, and the paper offers no attempt to validate or explain the claim.

The big tells

Figure 13 may offer the biggest clue to what is going on. The absence of No. 14 in the analysis discussion of Figure 13 is a serious logical inconsistency, or a major technical oversight, and concerning given the paper’s repeated claim that No. 14 is optimal across several modes of testing, including this one.

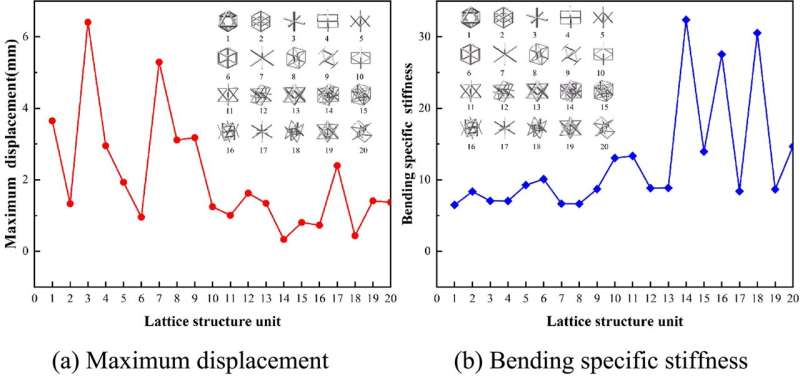

The paper states that Figure 13, “…presents the load-displacement curves under three-point bending. A considerable difference in deformation behavior was observed among the specimens. Specimen No. 3 exhibited the greatest bending deformation, reaching 6.44 mm, while Specimen No. 16 experienced the least deformation, recording only 1.278 mm. These results reflect differences in flexural stiffness, with Specimen 3 being the most compliant and Specimen 16 the most rigid under the same bending load.”

Figure 13 clearly shows No. 14 having the least deformation by far, yet is not mentioned.

Here, forensic clues to the potential evolutionary origin of the paper are revealed. Analysis highlights No. 3 and No. 16 as polar ends, highlighting No. 13 in torsion and 16 in bending. The analysis and data presented are correct, but only if the data line illustrated for No. 14 is ignored. One way this could have occurred is if the data lines for No. 14 were added after the analysis was written.

Figure 14 repeats the omission of No. 14 as it “…presents the load-displacement curves of lattice structure units under torsional conditions. Under the same applied load, Specimen No. 3 exhibited the largest angular displacement, measuring 32.608 mm, whereas Specimen No. 13 showed the smallest, at 0.428 mm. These findings reveal a wide range of torsional stiffness characteristics, with Specimen 3 demonstrating higher compliance and Specimen 13 exhibiting greater resistance to torsional deformation.”

As mentioned previously, “When subjected to torsion…” the paper claims No. 14 had a maximum displacement and deformation of 0.12 mm. This would make No. 14 the most resistant to torsional deformation, albeit with characteristics borrowed from No. 13.

Further adding to the confusion, Figure 15(c), No. 13 consistently shows slightly lower torsional displacement than No. 14 in both simulation and experimental data. The paper reports a significantly higher stiffness for No. 14, claiming it to be the top performer, a claim that cannot be mathematically nor visually supported given the paper’s own data recording.

This contradiction also undermines the validity of the paper and further supports the suspicion that No. 14’s performance values were adjusted post-analysis.

Figure 15(b) offers a chart overview of simulation versus experiment results in bending. Here No. 14 also shows the lowest displacement under bending for both simulation and experiment, making its earlier (Figure 13) absence all the more mysterious. Most figures and tables are infographics that lack the proper scale resolution to determine key differences and raw data is not provided.

Structural unit No. 10 was ultimately selected for actual robot application due to its light weight and overall characteristics. Authors conclude that their simulation results were in good agreement with the experimental outcomes, an indication that modeling techniques can be used to find further improvements.

The ever-skeptical writer of this article has a different conclusion, specifically that data may have been retrofitted into the study post hoc, post-analysis and after a first draft of the study was already completed. Possibly it is an example of a low-impact paper that then found a second life within the murky underworld of paper mill poofery, adding in a layer of fabricated significance to increase the impact of an otherwise expected finding.

All of this is speculation, which I will now water down with caveats, as this could be the result of poorly constructed data handling, AI formatting and translation issues, confounding of simulation and experimental modes, multi-author timepoint editing errors or a version error with an accidental publication of an early, unvetted pre-publication text.

Still, such a multitude of errors, inconsistencies and omissions, whatever the source, should have been spotted by the authors submitting their own work, peer reviewers taking their role seriously and the editorial staff of a prominent publishing journal protecting the integrity of their content for their readers and the scientific community at large.

If this had been a Ph.D. thesis it would likely have been denied. If it had been a college, or even a high-school paper, it should have received a failing grade. If it were a boat, the hull would be made of spaghetti strainers. But perhaps, it was never meant to be read by anyone.

Scientific Reports is a prominent publication within Nature, and it should mark a proud accomplishment in a researcher’s career to be a named contributor in a paper accepted by the journal for publication. That a paper can be published without being read is a red flag for quality control and publishing integrity. A retraction should be imminent.

Written for you by our author Justin Jackson,

edited by Gaby Clark, and fact-checked and reviewed by Robert Egan—this article is the result of careful human work. We rely on readers like you to keep independent science journalism alive.

If this reporting matters to you,

please consider a donation (especially monthly).

You’ll get an ad-free account as a thank-you.

More information:

Huipeng Shen et al, Research on lower limb lightweight of bionic robot based on lattice structure unit, Scientific Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-14679-5

© 2025 Science X Network

Citation:

Simulation modeling and physical testing for latticed bionic limbs match, but is it a real study? (2025, August 25)

retrieved 27 August 2025

from https://techxplore.com/news/2025-08-simulation-physical-latticed-bionic-limbs.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.